|

|

By Yucheng Guo, Pixiang Qiu, Taoguang Liu

Tai Ji Quan is considered to be a part of traditional Chinese Wushu (a martial art) and comprises various styles that have evolved historically from the Chen, Yang, Wǔ, Wú, and Sun families (schools). Recent simplification of the original classic styles has made Tai Ji Quan easier to adopt in practice. Thus, the traditional legacy of using Tai Ji Quan for self-defense, mindful nurturing of well-being, and fitness enhancement has been expanded to more contemporary applications that focus on promoting physical and mental health, enhancing general well-being, preventing chronic diseases, and being an effective clinical intervention for diverse medical conditions. As the impact of Tai Ji Quan on physical performance and health continues to grow, there is a need to better understand its historical impact and current status. This paper provides an overview of the evolution of Tai Ji Quan in China, its functional utility, and the scientific evidence of its health benefits, as well as how it has been a vehicle for enhancing cultural understanding and exchanging between East and West.

Tai Ji Quan (also known as Tai Chi) has traditionally been practiced for multiple purposes, including self-defense, mindful nurturing of well-being, and fitness enhancement. For hundreds of years the Chinese have enjoyed many benefits that Tai Ji Quan is believed to offer. Today, people of all ages and backgrounds from around the world are discovering what the Chinese have known for centuries: that long-term sustained practice of Tai Ji Quan leads to positive changes in physical and mental well-being. As both the popularity and impact of Tai Ji Quan on health continue to grow in China and worldwide, there is a need to update our current understanding of its historical roots, multifaceted functional features, scientific research, and broad dissemination. Therefore, the purposes of this paper are to describe: (1) the history of Tai Ji Quan, (2) its functional utility, (3) common methods of practice, (4) scientific research on its health benefits, primarily drawn on research conducted in China, and (5) the extent to which Tai Ji Quan has been used as a vehicle for enhancing cultural understanding and exchanging between East and West.

Tai Ji Quan, under the general umbrella of Chinese Wushu (martial arts),1 has long been believed to have originated in the village of Chenjiagou in Wenxian county, Henan province, in the late Ming and early Qing dynasties.1, 2, 3 Over a history of more than 300 years, the evolution of Tai Ji Quan has led to the existence of five classic styles, known as Chen, Yang, Wǔ, Wú, and Sun.

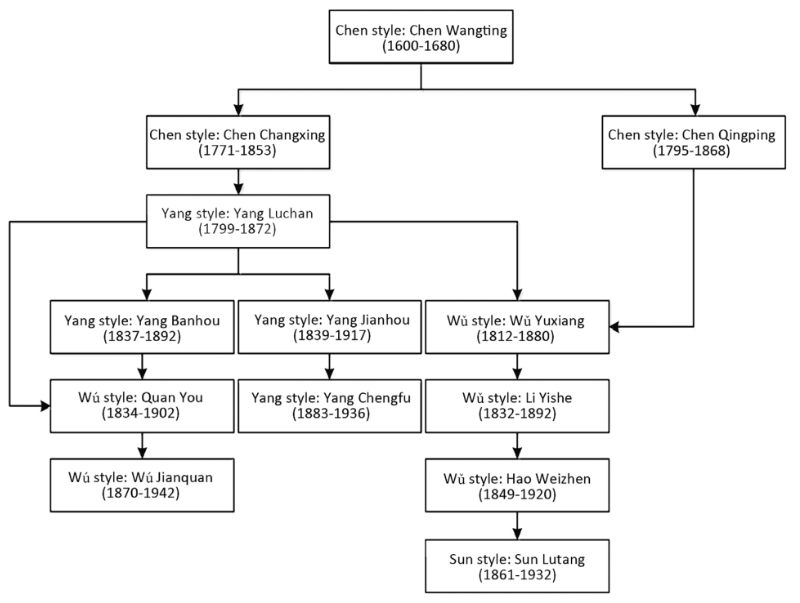

At its birthplace in Chenjiagou, Chen Wangting (1600–1680) has historically been recognized as the first person to create and practice Tai Ji Quan, in a format known as the Chen style.3 With the establishment of Chen style, traditional Tai Ji Quan begins to evolve both within and outside the Chen family. Chen Changxing (1771–1853) broke his family's admonitions to keep the art within the family by teaching Chen style to his talented and hard-working apprentice Yang Luchan (1799–1872) from Yongnian in Hebei province. Yang Luchan later created the Yang style and passed his routine to two of his sons, Yang Banhou (1837–1892), who developed the "small frame" of the Yang style, and Yang Jianhou (1839–1917). Yang Jianhou's son, Yang Chengfu (1883–1936), introduced Yang style to the public.4

Wǔ Yuxiang (1812–1880), who first learned Tai Ji Quan from his fellow villager Yang Luchan, acquired a thorough knowledge of Tai Ji Quan theory from master Chen Qingping (1795–1868) and, with assistance from his nephew Li Yishe (1832–1892), combined techniques he learned from both Yang and Chen styles to eventually develop the Tai Ji Quan theory that led to the formation of his unique Wǔ style.5

The fourth of the five main styles is Wú, which was created by Quan You (1834–1902) and his son Wú Jianquan (1870–1942). Quan first learned Tai Ji Quan from Yang Luchan and Yang Banhou. Wú's refinement of Yang's "small frame" approach gave rise to the Wú style.6

The fifth and most recent style of Tai Ji Quan comes from Sun Lutang (1861–1932), who learned Tai Ji Quan from the Wǔ style descendant Hao Weizhen (1849–1920). By integrating Xing Yi Quan and Ba Gua Zhang (two other forms of Chinese Wushu), Sun Lutang developed his unique Sun style.7 A schematic summarizing the history and evolution of the five classic Tai Ji Quan styles is presented in Fig 1.

Fig. 1. Summary of the evolution of the five classic Tai Ji Quan styles.

In summary, with its rich history and diversity of styles, Tai Ji Quan offers an exercise and/or sport modality that has long been thought to promote health, encourage cultural exchange, and help with disease prevention. Since the 1950s, under sponsorship of the Chinese State Physical Culture and Sports Commission, further modifications have occurred including varying the number of movements (24-form, 42-form, 48-form, 88-form).1, 8 Of these, the 24-form is the most frequently used in public programs and public health promotion. Subsequent development has further simplified the 24-form routine into 8- and 16-form routines.1

With its strong roots in Wushu, Tai Ji Quan is often practiced as a self-defense program that involves combative actions such as kicking, striking, subduing, and pushing down. These techniques must be skillfully executed through careful movement control and maneuvering rather than through overt external physical force.

Because Tai Ji Quan involves dynamic actions with controlled movements and coordination, long-term sustained practice is believed to improve the function of the nervous, cardiovascular, respiratory, and musculoskeletal systems, thus enhancing physical fitness, preventing chronic disease, improving overall quality of life, and increasing longevity.

The foundation of Tai Ji Quan has deep roots in ancient Chinese philosophies of Confucianism and Taoism, which have been embraced in various cultural practices such as traditional Chinese medicine. The blending of focused physical activity with breathing exercises in Tai Ji Quan has long been thought to nurture the full integration of body, mind, ethics, and behavior. As Tai Ji Quan involves deliberately executed movements that are slow, continuous, and flowing, it results in calmness, the release of stress and tension, and heightened awareness of the body in relation to its environment. Therefore, the sustained practice of Tai Ji Quan is thought to help promote psychological well-being.

Tai Ji Quan has also been used for sporting purposes that often involve elements of theatre and competition. For example, as a cultural manifestation of Wushu, Tai Ji Quan was performed by a cast of thousands during the opening ceremony of the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing.

With the growth of Tai Ji Quan, standards and classifications have been developed for certifying practitioners in all classic styles.3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Similarly, standardized forms have been created, including the well-known simplified 24-form, and push-hand and sword routines. Tai Ji Quan has been included as a formal event in many local, national, and international tournaments, including the Asian Games, both Junior and Open World Wushu Championships, and Jiaozuo International Tai Ji Quan Exchange Competition, which provide performance and competition platforms for Tai Ji Quan practitioners at various levels to share their expertise.

Because Tai Ji Quan is often practiced in groups in public places such as community centers, parks, and plazas, it offers a unique opportunity for the exchange of ideas, social networking, and developing social and personal relationships among practitioners. Its increasing popularity internationally has made Tai Ji Quan a resource for promoting cultural exchange and appreciation.

Like Wushu, Tai Ji Quan serves multiple functions, from the traditional practice of self-defense to its contemporary uses for promoting public health, enhancing quality of life, and facilitating cultural exchange. The multidimensional nature of Tai Ji Quan makes it well suited for people from all walks of life.

Static-stance practice is a fundamental skill for practitioners of Tai Ji Quan. The most common types of static-stance practice are Wuji pylon stance (the preparatory form or opening stance of Tai Ji Quan), Chuan-character pylon stance, and the palm pylon stance. Practicing the static stances not only builds the strength of the legs and hips but also helps establish a sound posture and foundation for learning and practicing more complicated forms/movements.

The single-form practice is the most basic way of learning and practicing Tai Ji Quan. For example, Cloud Hand uses the waist as a pivot and drives the arms for coordination, exercising the torso and shoulder joints. The single-form practice can also be used to alleviate pain and fatigue in specific parts of the body. Thus, for individuals who work at a sedentary job, the single-form practice may be a good method for reducing fatigue.

Combination practice refers to practice of movements contained within a form. Repetitive practice of the movements (ward-off, rollback, press, push) involved in the form "Grasp the Peacock's Tail" exemplifies this. Combination practice plays an important role in mastering correct actions as well as developing basic skills for engaging in more complicated routines (described below). In addition, this practice expands the number muscles and joints involved, thereby extending the benefits of improving flexibility, reducing fatigue, and enhancing fitness.

Routine practice represents a mainstream training method that involves practicing Tai Ji Quan in accordance with its original sequence (e.g., 24 forms). This typically begins with a particular starting form and finishes with a predefined ending form.

The push-hand practice is a barehanded training routine performed between two practitioners. Practice of push-hand can be divided into several forms, including fixed-step push-hand, single-hand push, double-hand push, and moving-step push-hand, which requires coordination of the upper and lower limbs. The basics of the push-hand practice are developed through eight techniques, including warding off, rolling back, pressing, pushing, plucking (or grasping), splitting, elbowing, and leaning. Push-hand practice is often viewed as a way of evaluating the extent to which Tai Ji Quan techniques are performed or have been mastered in accordance with pre-specified standards.

There are multiple practice options involved in Tai Ji Quan, all of which are essential for learning and mastering its fundamentals. The most common include static-stance, single-form, combination, routine, and push-hand.

Because Tai Ji Quan involves carefully controlled and executed physical movements, it has long been suggested that various health benefits are derived from its practice.9, 10, 11 Despite its long history, evidence of these benefits has been mostly anecdotal. During the last 2 decades, however, an increased effort to clarify the health effects of Tai Ji Quan has been made through scientific studies, including both observational and experimental research. The following section provides a brief review of the research evidence drawn primarily from studies conducted in China.

Regular practice of Tai Ji Quan has been shown to lower blood pressure, improve lipid metabolism,12, 13 reduce cardiovascular risk factors in patients with dyslipidemia,14 protect the cardiovascular system, and improve hemodynamic biomarkers of blood viscosity.15

Studies of Tai Ji Quan have indicated that it has a positive influence on protecting lymphocytes and enhancing immunoregulation of cells thereby improving cellular immune function, especially for middle-aged and older adults.16, 17 For example, Yeh et al.18 found that after 12 weeks of training, Tai Ji Quan participants showed a significant increase in the ratio of T-helper to cytotoxic (CD4:CD8) and regulatory (CD4:CD25) T-cells. A recent pilot study also showed that a 16-week Tai Ji Quan intervention significantly attenuated CD55 expression (decay-accelerating factor) among post-surgical non-small-cell lung cancer survivors.19

Tai Ji Quan practice, as an aerobic exercise at low to moderate intensity and with long-term duration, has been found to enhance cardio-pulmonary function in terms of improved vital capacity, maximum ventilatory capacity, and oxygen consumption.20, 21, 22, 23

Tai Ji Quan has been shown to have a beneficial effect on balance, or on delaying the decline of balance capacity, in middle-aged and older adults.24, 25 Specifically, studies have shown that Tai Ji Quan helps improve vestibular function, static balance, muscular strength, proprioception, physical agility and coordination skills, consequently reducing the frequency of falls.26, 27, 28, 29, 30

There is some evidence suggesting that Tai Ji Quan may be an effective, safe, and practical intervention for maintaining bone mineral density.9, 31 For example, two randomized controlled trials indicated that Tai Ji Quan practice helped retard bone loss in early postmenopausal women.32, 33 However, at the moment the evidence is inconclusive given the contradictory findings of a separate randomized controlled trial of older adults.34

The health benefits of Tai Ji Quan for patients with cancer are unclear, in part due to the lack of research in this area, but promising. For example, a recent pilot randomized controlled study19 conducted in Shanghai showed that a 16-week Tai Ji Quan training program for non-small-cell lung cancer patients significantly lowered CD55 expression, which has been shown to negatively impact T-cell function.35, 36 Additionally Tai Ji Quan training has been found to improve shoulder strength and functional well-being in breast cancer survivors.37

A recent review of the literature suggests that Tai Ji Quan may be effective in dealing with negative emotions and psychological disorders such as depression, anxiety, hostility, and delusion.38 For example, in a small-scale randomized controlled trial, Cho reported that a 12-week Tai Ji Quan program reduced depressive symptoms, including somatic and psychological symptoms, related to interpersonal relationships and well-being in a sample of older patients with major depression.39 Tai Ji Quan training has also been shown to improve self-esteem and psychological components of health-related quality of life among nursing home residents40, 41 and to alleviate the negative psychological impact stemming from natural disasters.42

Regular practice of Tai Ji Quan can improve sleep quality. For example, Yang43 found that Tai Ji Quan practice helped overcome sleep disorders and shortened the time it took college students to fall asleep.

To date, two randomized controlled trials have shown that Tai Ji Quan training can have a positive effect on brain volume and cognition in older adults. In one study, Tai Ji Quan practice resulted in significant increases in brain volume and improvements in memory and executive function in a sample of Chinese elders without dementia,44 while a further study showed that Tai Ji Quan reduced the risk of developing dementia while improving memory and executive function in older Chinese adults at risk of cognitive decline.45

There is an increasing amount of empirical evidence showing that Tai Ji Quan improves health-related outcomes in adult populations.

Since the 1950s, Tai Ji Quan has attracted tremendous interest worldwide. This is partly due to efforts made by the Chinese to use Tai Ji Quan as a bridge to connect its culture to the rest of the world, especially the West. Several areas in which Tai Ji Quan has helped bridge the East-West divide are described below.

Various efforts have been made to employ educational institutions and cultural centers to promote Tai Ji Quan internationally, including using the Confucius Institute as an outlet for dissemination. The mission of the Confucius Institute is to forge exchanges of language, culture, and research in countries with different cultural backgrounds. Information gathered from the Fourth Confucius Institute Conference in 2009 indicated that, among the 217 Confucius Institutes (and classrooms) having a presence at the conference, nearly 30% offered Wushu courses, including Tai Ji Quan. By offering opportunities to learn Tai Ji Quan, these institutes have advanced cultural understanding of traditional China through scholarly exchanges and collaborative research efforts.

Because of the potential of Tai Ji Quan to enhance various aspects of health, there has been an increase in cooperation among research and academic scholars in East and West. A recent joint study by international researchers on the connections between Tai Ji Quan and brain health of older adults in Shanghai, China, is representative of this international collaboration.43 Conferences or symposia on Tai Ji Quan have also provided a platform for exchanging knowledge and expertise among scientists, researchers, and clinicians interested in the applications of Tai Ji Quan in community and clinical practice.

Each year various international competitions are held involving Tai Ji Quan, often integrated into Wushu events. Sponsored either by private or government organizations and attracting large numbers of competitors, some of the more well-known events include the Shaolin International Wushu Festival, Hong Kong International Wushu Festival, and World Traditional Wushu Festival. In 2013, the annual Jiaozuo International Tai Ji Quan Exchange Competition in China attracted over 3500 competitors from more than 30 countries and regions.

Tai Ji Quan has also been used to create cultural exchanges among people of different races, religions, and cultures. For example, World Tai Ji Quan Day, held on the last Saturday of April, was first organized in 1999 and is now observed annually by Tai Ji Quan enthusiasts worldwide. Its aim is to promote Tai Ji Quan culture and health. Tai Ji Quan and other forms of Wushu have been used to promote international relationships and friendships. For example, during an event called Chinese Culture Focusing on Africa, Chinese Wushu specialists delivered demonstrations of Tai Ji Quan and Wushu on trips to South Africa and Liberia. Similarly, in events promoting the theme of "Peace, Friendship, and Health" sponsored by the Chinese Wushu Association and the Permanent Mission of China to the United Nations in 2013, Chinese Wushu artists provided a performance attended by more than 1600 international guests.46

Originating in China several hundred years ago, Tai Ji Quan has gained international recognition and is now practiced by millions of people worldwide for health improvement, performance/competition, and cultural understanding. Dissemination of Tai Ji Quan has narrowed cultural gaps between China and the West, and has offered opportunities to connect people from different cultural backgrounds to promote health and enjoy performances of this ancient art.

From its classic status as a martial art in ancient times to its diverse applications in the modern era, Tai Ji Quan has undergone a continual process of evolution, refinement, integration, and standardization. With increased recognition of its historical value and health-enhancing potential, Tai Ji Quan is making contributions in the areas of performance, biomedical research, and community health promotion through contemporary applications. Tai Ji Quan has clear potential to build on its existing reputation for optimizing and enriching human health and well-being.

The work presented in this article was supported by a grant from the National Social Science Foundation of China (No. 12BTY052). The authors wish to express appreciation to Shuang Wang, Xiaoxin Ma, Wenjing Zhai, Amber Ziqian Li, and Fuzhong Li for their assistance and constructive feedback and suggestions during the various stages of writing this manuscript.

Bibliographic information about this article.

Authors: Yucheng Guo, Pixiang Qiu, Taoguang Liu. Title: “Tai Ji Quan: An overview of its history, health benefits, and cultural value.” Source: Journal of Sport and Health Science, Volume 3, Issue 1, 2014, pages 3-8. ISSN 2095-2546. Online at: https://doi.org and https://www.sciencedirect.com/

and https://www.sciencedirect.com/ .

©2014 Shanghai University of Sport. Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.

Open access under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND license.

.

©2014 Shanghai University of Sport. Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.

Open access under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND license.

Committee of Chinese Sports College Textbook. Chinese Wushu Textbook (Part I). Beijing: People’s Sports Publishing House of China; 2003.

Committee of Chinese Wushu Encyclopedia. Chinese Wushu Encyclopedia. Beijing: Encyclopedia of China Publishing House; 1998.

Wushu Research Institute of the General Administration of Sport of China. Textbook Series of Chinese Wushu Duanwei System: Chen-Style Taijiquan. Beijing: Higher Education Press; 2009.

Wushu Research Institute of the General Administration of Sport of China. Textbook Series of Chinese Wushu Duanwei System: Yang-Style Taijiquan. Beijing: Higher Education Press; 2009.

Wushu Research Institute of the General Administration of Sport of China. Textbook Series of Chinese Wushu Duanwei System: Wu-Style Taijiquan. Beijing: Higher Education Press; 2009.

Wushu Research Institute of the General Administration of Sport of China. Textbook Series of Chinese Wushu Duanwei System: Wu-Style Taijiquan. Beijing: Higher Education Press; 2009.

Wushu Research Institute of the General Administration of Sport of China. Textbook Series of Chinese Wushu Duanwei System: Sun-Style Taijiquan. Beijing: Higher Education Press; 2009.

Qiu PX. The Knowledge Questions and Answers of Taijiquan Practice. Beijing: The People’s Sports Press; 2001.

China Sports. Simplified “Taijiquan”. Beijing: Foreign Language Printing House; 1980.

Lan C, Lai JS, Chen SY. Tai Chi Chuan: an ancient wisdom on exercise and health promotion. Sports Med. 2002;32:217–24.

Li JX, Hong Y, Chan KM. Tai Chi: physiological characteristics and beneficial effects on health. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35:148–56.

Wang ZS, Su ZP, Yuan X. Tracing study of blood circulation, blood fat and serum calcium, phosphorus for old men playing Taijiquan. J Tianjin Inst Phys Educ. 1994;9:1–6. [in Chinese]

Tsai JC, Wang WH, Chan P, Lin LJ, Wang CH, Tomlinson B, et al. The beneficial effects of Tai Chi Chuan on blood pressure and lipid profile and anxiety status in a randomized controlled trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2003;9:747–54.

Lan C, Su TC, Chen SY, Lai JS. Effect of T’ai Chi Chuan training on cardiovascular risk factors in dyslipidemic patients. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14:813–9.

Wang ZS. Research of effects of Taichichuan on plasma lipids and hemorrheological indicators in older adults. J Tianjin Inst Phys Educ. 1999;14:51–3. [in Chinese]

Liu XD. Influence of 8-week Tai Chi Chuan on immune function of older people. Chin J Clin Rehabil. 2006;10:10–1. [in Chinese]

Liu SH, Zhang H. The research on the effect of Tai Chi exercise on T lymphocyte subgroup and NK cells. China Sport Sci Tech. 2002;38:50–2. [in Chinese]

Yeh SH, Chuang H, Lin LW, Hsiao CY, Eng HL. Regular Tai Chi Chuan exercise enhances functional mobility and CD4CD25 regulatory T cells. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:239–43.

Zhang YJ, Wang R, Chen PJ, Yu DH. Effects of Tai Chi Chuan training on cellular immunity in post-surgical non-small cell lung cancer survivors: a randomized pilot trial. J Sport Health Sci. 2013;2:104–8.

Jia SY, Wang ML. Effects of Changquan and Taichiquan exercises on cardiorespiratory function of male college students. China Sport Sci Tech. 2008;6:51–5. [in Chinese]

Lai JS, Lan C, Wong MK, Teng SH. Two-year trends in cardiorespiratory function among older Tai Chi Chuan practitioners and sedentary subjects. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:1222–7.

Lan C, Lai JS, Chen SY, Wong MK. 12-month Tai Chi training in the elderly: its effect on health fitness. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:345–51.

Wei Y, Chen PJ, Tian ML. Change of ahead and behind 6-month Tai Chi exercise to middle-aged and old women related parameters of cardiopulmonary function. Chin J Sports Med. 2007;5:604. [in Chinese]

Leung DP, Chan CK, Tsang HW, Tsang WW, Jones AY. Tai Chi as an intervention to improve balance and reduce falls in older adults: a systematic and meta-analytical review. Altern Ther Health Med. 2011;17:40–8.

Wong AM, Lan C. Tai Chi and balance control. Med Sport Sci. 2008;52:115–23.

Fong SM, Ng GY. The effects on sensorimotor performance and balance with Tai Chi training. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87:82–7.

Li JX, Xu DQ, Hong YL. Effects of 16-week Tai Chi intervention on postural stability and proprioception of knee and ankle in older people. Age Ageing. 2008;37:575–8.

Liu J, Wang XQ, Zheng JJ, Pan YJ, Hua YH, Zhao SM, et al. Effects of Tai Chi versus proprioception exercise program on neuromuscular function of the ankle in elderly people: a randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012:265486. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/265486

Tsang WW, Hui-Chan CW. Effects of Tai Chi on joint proprioception and stability limits in elderly subjects. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1962–71.

Xiao CM, Wang T, Jiang GP. Research on impacts of Taijiquan on the balance ability of the aged people. J Beijing Sport Univ. 2006;4:490. [in Chinese]

Wang ZS. A tracking study of bone development in older people exercising Taijiquan. Sports Sci. 2000;20:79–81.

Chan K, Qin L, Lau M, Woo J, Au S, Choy W, et al. A randomized, prospective study of the effects of Tai Chi Chun exercise on bone mineral density. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:717–22.

Zhou Y. The effect of traditional sports on the bone density of menopause women. J Beijing Sport Univ. 2004;27:354–60. [in Chinese]

Woo J, Hong A, Lau E, Lynn H. A randomized controlled trial of Tai Chi and resistance exercise on bone health, muscle strength and balance in community-living elderly people. Age Ageing. 2007;36:262–8.

Heeger PS, Lalli PN, Lin F, Valujskikh A, Liu J, Muqim N, et al. Decay-accelerating factor modulates induction of T cell immunity. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1523–30.

Liu J, Miwa T, Hilliard B, Chen Y, Lambris JD, Wells AD, et al. The complement inhibitory protein DAF (CD55) suppresses T cell immunity. In Vivo J Exp Med. 2005;201:567–77.

Fong SSM, Ng SSM, Luk WS, Chung JWY, Chung LMY, Tsang WWN, et al. Shoulder mobility, muscular strength, and quality of life in breast cancer survivors with and without Tai Chi Qigong training. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:787169. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/787169

Zhang L, Layne C, Lowder T, Liu J. A review focused on the psychological effectiveness of Tai Chi on different populations. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:678107. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/678107

Cho KL. Effect of Tai Chi on depressive symptoms amongst Chinese older patients with major depression: the role of social support. Med Sport Sci. 2008;52:146–54.

Lee LY, Lee DT, Woo J. Effect of Tai Chi on state self-esteem and health-related quality of life in older Chinese residential care home residents. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:1580–2.

Lee LY, Lee DT, Woo J. The psychosocial effect of Tai Chi on nursing home residents. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:927–38.

Yang XY. Effects of shadowboxing exercise on the senior citizens’ mental health recovery after earthquake. J Beijing Sport Univ. 2010;6:77. [in Chinese]

Yang XQ. Experimental study of the effect of Taijiquan on psychological health of college students. J Tianjin Inst Phys Educ. 2003;18:64. [in Chinese]

Lam LC, Chau RC, Wong BM, Fung AW, Tam CW, Leung GT, et al. A 1-year randomized controlled trial comparing mind-body exercise (Tai Chi) with stretching and toning exercise on cognitive function in older Chinese adults at risk of cognitive decline. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:568.e15–20.

Mortimer JA, Ding D, Borenstein AR, DeCarli C, Guo Q, Wu Y, et al. Changes in brain volume and cognition in a randomized trial of exercise and social interaction in a community-based sample of non-demented Chinese elders. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;30:757–66.

Permanent Mission of the People’s Republic of China to the UN. Peace, Friendship, and Health. Available at: http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/ce/ceun/chn/gdxw/t849964.htm [accessed 16.09.2013].

|

Related: Qi | Modified: 04/22/2025 |